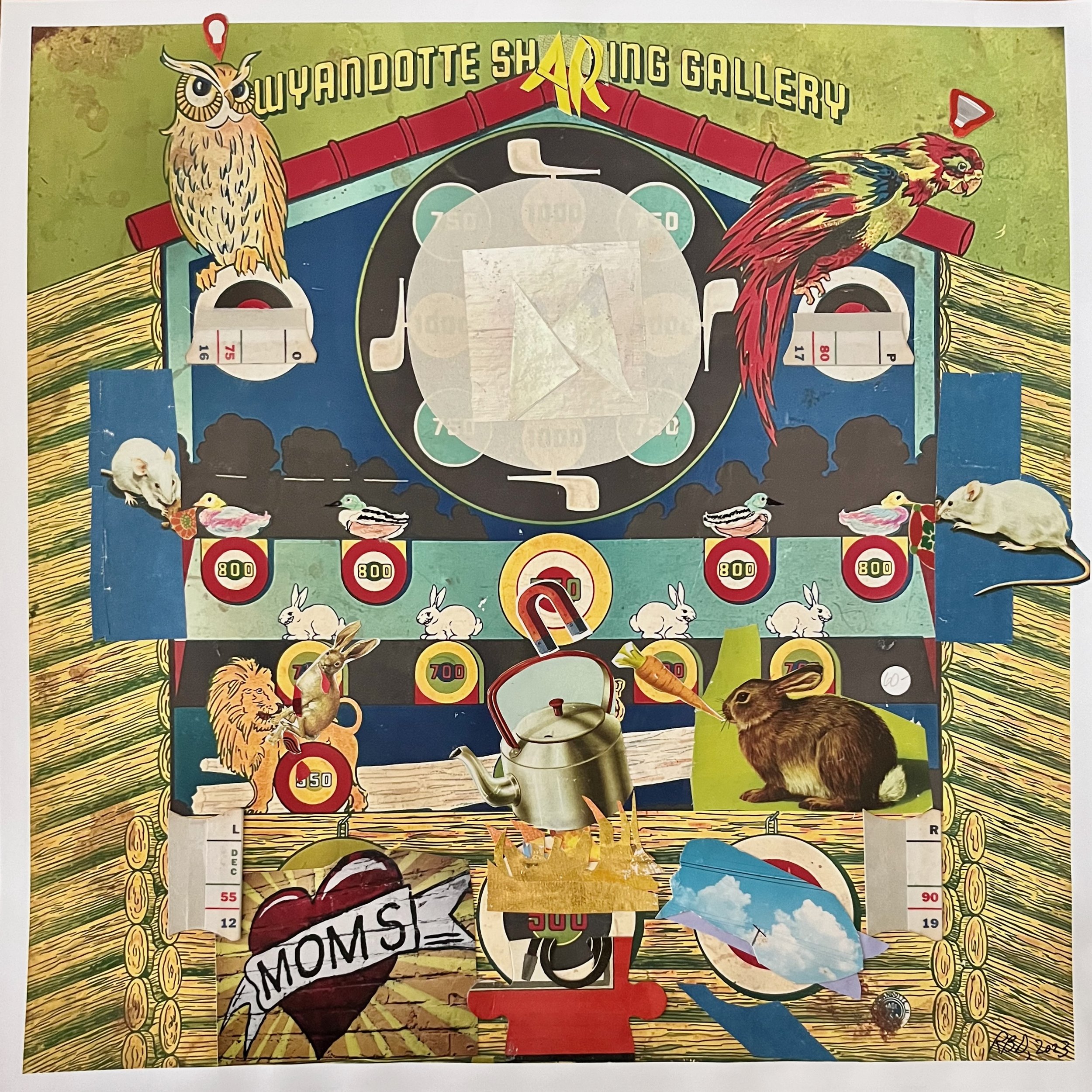

A Note on the Game Board “Shooting Gallery,” Ashbery’s Game Board Collage “Circus Friends,” and My Collage “Wynandotte Sharing Gallery.”

—Rachel Blau DuPlessis

NOTE: The Flow Chart Foundation’s Ashbery Resource Center has a collection of antique game boards and other materials that John Ashbery had used for his collages. In 2023, a group of artists and poets were invited to make new collages using some of these materials: ”Ashbery Collage Collages.” Rachel Blau DuPlessis created a collage using as a background a print made from the “Wyandotte Shooting Gallery” game board, the same one used by Ashbery his collage “Circus Friends.” The following essay was written to be given to the winning bidder of her collage, and we were also given permission to reprint it here.

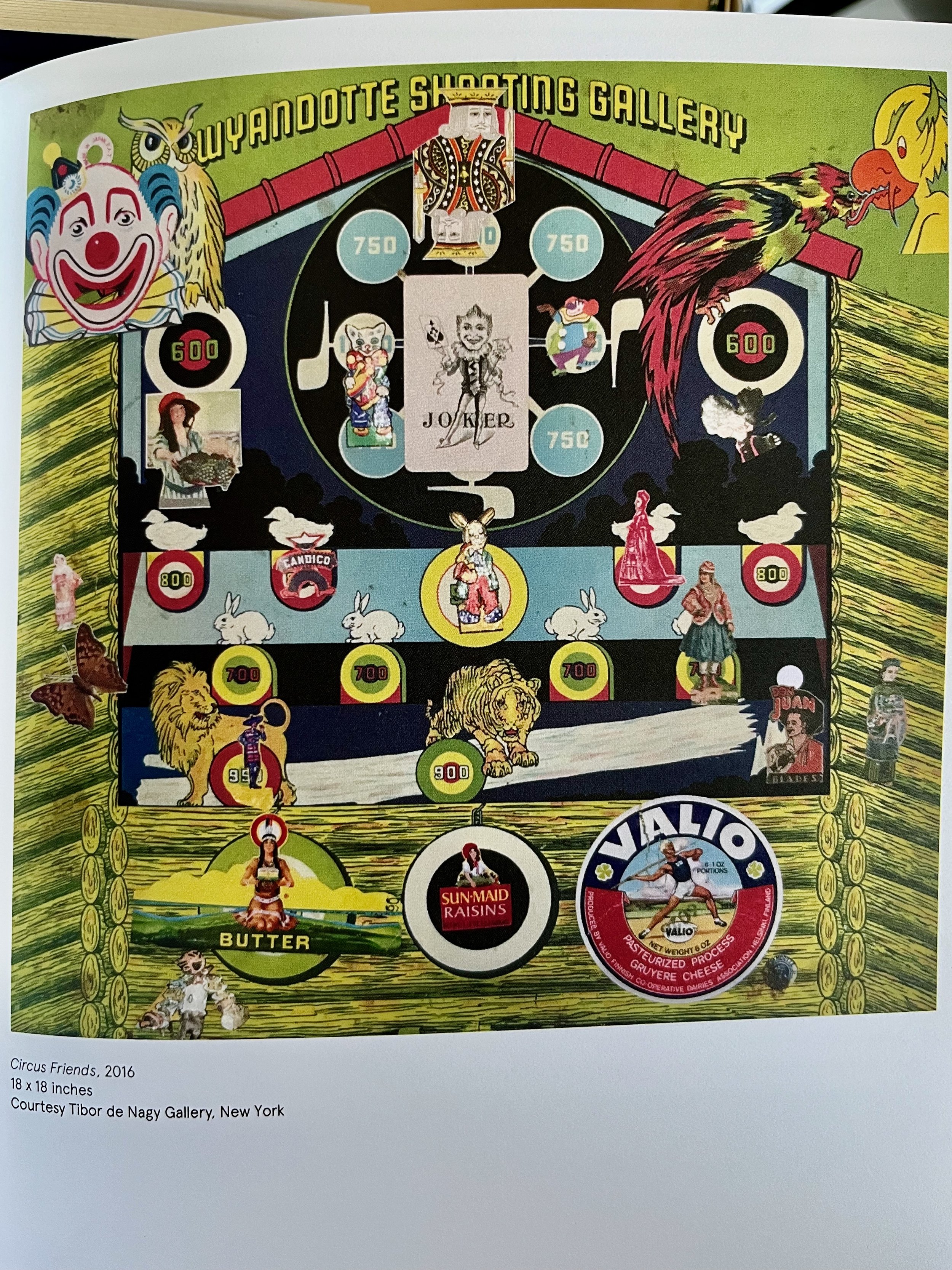

[above, L to R: Shooting gallery game board, collage by Rachel Blau DuPlessis, collage by John Ashbery (from They Knew What They Wanted Rizolli book of Ashbery collages)]

In 2023, the Flow Chart Foundation fundraising initiative—suggested by Susan Bee—was to ask some artists, and people who make collage to use a matrix that John Ashbery himself used for one of his game board collages.

Ashbery himself did not want to use up those game board matrices by collaging directly on them, and thus the assignment involves both an extant collage by Ashbery as well as the game board in Ashbery’s archive/attic. That is, when he used a game board, he had the item photographed, full size, in color. In 2023. Jeffrey Lependorf of Flow Chart Foundation provided that matrix (that is, a photograph of the game board) assigned to each person who was doing a fun/fundraising collage.

On the back of the finished collage that I contributed I put the following description:

Wyandotte Shooting Gallery (a game board, not dated) with John

Ashbery’s Circus Friends, a 2016 collage, in mind, has been

collaged for this Flow Chart Foundation fun/Fund Raiser.

becoming Wyandotte Sharing Gallery by RBD [Rachel Blau DuPlessis]

in her 2023 imagination. Still 18 x 18 inches, with added joss paper,

pictures of vegetables, animals and a kettle from a British alphabet

poster and a collaging book of cut-outs, several postcard elements,

cardboard packaging, and an index-sorter from vintage office supplies.

Now any person asked by Jeffrey Lependorf was certainly aware of—and even deeply committed to—John Ashbery, his poetic oeuvre (itself intricately scintillating with collage strategies—but also with rich syntaxes), and was at least aware of his collages and other visual materials, his tchotke-sensibility and hoarder’s temptations. In short, any responding artist plausibly had already negotiated with Ashbery’s collages, their often flirtatious force, their charms, flair and sense of materials and the allusions—high, medium, pop, low, cross-cut, zany, offering visual pleasure or pique. As with much allusive art, the more you know of the stylistic choices, the visual languages, the eras from which the collage cutouts come, the richer, more overloaded, and possibly unresolvable a collage becomes. In Ashbery, the array of his collages will generally exceed interpretation, and (like his poems) be “about” their own being, their embodied or ongoing presence. Some of them , however, often those made from postcards, do tell oblique, suggestive anecdotes.

The assigned artists were not asked to connect with or respond to Ashbery’s finished collage, or to “remake” that, but rather to take their inspiration and investigation from the pre-Ashbery’d game board matrix. On the other hand, it would take a falsifying erasure of what these makers probably know, might have seen, and even could have an opinion about to resist that Ashbery Elephant in this collage room. One could not help but somehow “know” his collaging practices. Here’s what was on my mind given my game board. First off, since the game was a “shooting” game—most likely with darts (not included) or an air gun loaded with corks (also not included)–this board mainly showed stylized representations of animals, fowl, and birds, mini-targets set under them, with the worth of a hit in hundreds—600 points, 800 points, and so forth. The main impression was creatures (wild, exotic, domesticated), and numbers, lined up, rather squared off all in a log-cabin structure—that shooting booth or shooting gallery. I was the party-pooper resistant to a game of shooting, of shooting animals, and of the numerical totals that could be racked up. Wary but really weary. Too many numbers, too many targets. So this particular game now left me amused but indifferent. Yet it was stylized correctly—with wild animals worth more, plus rows of anodyne targets—ducks for example, that in actual games in arcades circle around on a mechanical cog device.

What interested me was the mystery Noun. Wyandotte—the name of the shooting gallery on the board—that alludes to two relevant associations. It was the name given to a tribal merger of Indians around the Great Lakes region—Huron and Petun tribes. These tribes were said (as just about all native Americans were) to be “fierce warriors.” Thus the shooting gallery as a test of skill with us as warriors, possibly in buried allusion to US settler-fighters eager to take on the Indians. The pine log cabin booth was meant to evoke rustic bravery at the point of a gun in a (this will date me) Davy Crockett mode. The place name recalls that tribal merger, Great Lakes and south. The second main association is that skill game likely alludes to the Wyandotte County Fair held every July in Kansas City, including booths, skill and luck games, food galore, and a show of farm animals and fowl, with crafts also—ribbons competed for. (Plus, the game board might also have been manufactured in Wyandotte, Michigan.)

In the irreverent and juxtaposing spirit that Ashbery induces, I note also that the Wyandotte chicken is apparently a pleasant, calm breed, good for both eggs and meat. And in the pastoral mode of those chickens, if I confess that a shooting game is not to my current taste, I would have to admit that as a child, I did have a cap pistol and a tomboy’s/cowboy’s sensibility. Yet those insistent target numbers all over the board (rather the idea of the game!) made me want to countermand that order—killing animals and birds, racking up points. I never liked math much—though numbers are OK. And “Bang, bang, You’re dead” has lost its appeal in the interim. My contrarian and annoying proposal, barely resisting sheer prissiness, was I didn’t want to play along with a Shooting Gallery although I love a good state fair. So I wobbled—given the existing title and its letters, between reconstructing a shaping or a sharing gallery. There were other verbal possibilities—shining gallery, shitting gallery, shoeing gallery. When I chose sharing (and collage-revised a few letters on my game board), that anodyne choice (as I had hoped) generated its own comedy, as when I made a rabbit offer a carrot to a lion, while at the same time, the lion must necessarily offer a tasty just-killed rabbit to the rabbit. Note the now grimacing, suspicious rabbits just above, too.

The symmetry of this game board (owl/parrot on top) and preserving that symmetry (by covering the tiger in the middle in favor of a kettle) allowed further narrative inference among rabbit(s) and lion. What MOMS is doing there is hard to say except the domestic virtues, including kettle, have scored some ironic points. Further, there’s a visual echo in the background between the Moms postcard and the log cabin. The color-saturated postcard cut of sky and clouds is echt homage to Ashbery, scissored as it was from a 1950s card celebrating a motel in Jacksonville, Florida.

Ashbery’s own game board collages are static collections—within a frame and set in that zone almost as if a scrapbook. There is little overlapping of the papers added by Ashbery; the point seems to have been to add materials into the zone, frame, or park represented by the board. Most of the additions are not going to meld with each other into a combined structure, with form and color and texture. The additions are treated as presentational icons. If enough icons are added into a collage, for this is a type within a typology of collage, the reader gets to construct some interpretive narrative—possibly causative sequences, some with interesting loose ends. There’s an Ashbery collage of the boy going to school being harried by a bird, and watched solemnly, raptly by two girls, one a toddler. Something (undepicted) then happens—on the way, in school, or somewhere and when the boy returns—he has a bird’s head, perhaps that bird’s head. This collage lends itself to “a reading.” Let’s just say, it evokes interesting plausibly mysteries, narrative possibilities, and seems to conclude: thing A occurs and when thing B then happens, there seems to be some causative, or superreal, force of event between them. (Perhaps stage-managed by a mysterious male adult lurking in the second collage.)

Most of Ashbery’s game boards don’t bother with creating those possibilities; his additions seem sometimes to be figures looking for their stories. A curiosity of the poet’s game board collages is that some of the boards are dedicated to friends, and often on the board, one suspects, is a token of that friendship, partnership, or a bit of paper that plausibly alludes to the friend or to their relationship. Because of some encoded comment he might be making and the wandering not always focused stuff he has added, his game boards are generally charming, but sometimes flat.

Allusion in collage is also variable and interestingly unstable—not necessarily consistently done for the same purpose or by drawing on the same type of material. In “Circus Friends” (Ashbery’s title for the collage he made from the same game board as the challenge Jeffrey Lependorf gave to me), the large stylized clown head in the upper corner juxtaposed with the [wise] owl reinforces the title.

There is often an incongruity of size in these works –a very exploitable characteristic of collage. In Ashbery’s Circus Friends some small upright figures wander away from the main territory, dispersing themselves. The visual and narrative impacts are as if the board is inhabited by an unlinked series of vignettes, or small groupings of linked allusive objects like the packaging he glued to “Circus Friends” –all round, but NOT targets—of a cheese, a butter package, and a raisin box.

That packaging’s potential roundness may have caused the circus zone to be chosen for Ashbery’s title and, I postulate, is a saturated choice, perhaps also resisting the incessant target, or at least “echoing, as they used to say, their roundness. Perhaps that Ashbery had to seek among his visual image collection (“I know there is a 5-inch Clown head around here somewhere”) different in its leading you from the round shapes of packaging whose source was (plausibly) things around because of lunch, now cut in circles to loosely allude, or not quite, to the targets or to balls for acrobats or animals to balance on.

In his collages, the vignettes are contained narratives (like the sentences in his poetry) but generally do not involve the whole board, rather a two or three item corner of a given work. Ashbery’s poetry often shifts into evocative versions of an array of events, by his heteroglossia and socially mobile allusions, and by his intricate syntax, causal or sequential, yet in these game board collages there are several presentations of material, but not necessarily connected ones, even by reader inference. They are like a puzzle across the endless surface of “things happen and happening,” things emerge here, now, in this space. There is not necessarily a reason or an important reason, nor a “syntax” that joins the items JA added. Syntax is a suggestive and complicating word to use about a collage, demands more analysis from me (or someone), and might be too structuring. Here I’ll take a rain check.

Ashbery’s vintage game boards feature points accumulated in a given game, present odd figures pasted around, and suggest evocative childhood memories; so even if the game is unknown to us, they are palpably items evoking nostalgia. They also have a “framed” squared-offedness uncharacteristic of Ashbery’s flowing poetries. I saw many at the Pratt exhibit [NYC, November 2018], and I noted these features again in the book of Ashbery’s collages. This book, that has many of these collaged game boards (but not his Circus Friends), is They Knew What They Wanted: Poems and Collages. Ed. Mark Polizzotti, introduction and interview of Ashbery by John Yau. NY: Rizzoli/ELECTRA, 2018.

Talking about collage in general here (and in Ashbery’s game board works particularly), what struck me as general categories for collage interpretation are scale, zone created, vignette-narratives and/or syntaxes, and provenance, combined with the stylistic and social powers of visual allusion. These five categories are concepts useful for collage in general, their materials and arrangements, but in this case are a motivation to look closely at the histories and sources of the materials as they hover and weave into possible, but never completed, interpretations.

—Rachel Blau DuPlessis, July 2023 rachel.duplessis@temple.edu